Beyond the Horizon

This is one of the most interesting yachts I know: She is unusually comfortable at sea, in any climate. She is one of the safest pleasure yachts of her size, designed to be as simple and reliable as possible. And she sails just fine, despite not having a ‘proper’ deep keel.

An unusual set of properties like these obviously do not happen by themselves. In the case of the ATOA, they are in part the result of some extremely careful planning and engineering. But, to some extent they are also the result of coincidence. How did this happen?

The Atoa 64 was conceived as a competent expedition yacht – ATOA refers to Arctic to Antarctic. With a visit to the Amazon river on the way so we could perhaps have called her Atoama. The requirements were very specific:

Design Parameters

- A fast passagemaker, at least 8 knots average offshore under engine or sail – off the wind or to windward!

- Draft limited to 1,60 m and able to dry out, self-supported, in tidal waters.

- Protected propeller, good for all sorts of conditions

- Completely self-reliant.

- Foolproof keel, rudder and rig. As long as the keel, rudder and rig stays on a boat, the boat will usually be fine

- Immensely strong construction, capable of handling any weather without damage and able to go through thin ice.

- A double-ended stern was desirable, if it did not detract from the basic qualities

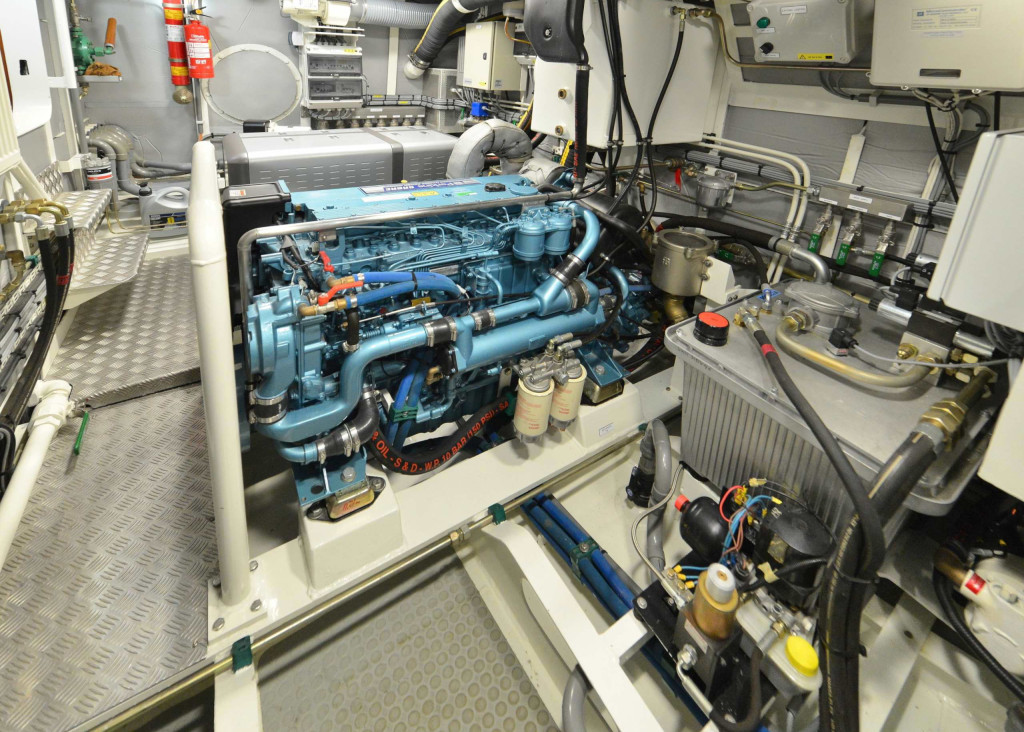

- A walk-in engine room, possible to do maintenance and repairs on site

- A completely enclosed pilot house from which the yacht could be handled for long periods in adverse weather.

- Cockpit as sheltered as ever possible.

- Easily handled by one or two persons

- Three cabins, one of which could be used as a crew cabin, with en-suite layout

During the project phase, all sorts of different concepts were evaluated. Our client suggested twin keels – these were ruled out for their inherently lacklustre performance. A ballasted swing keel was deemed too vulnerable, and handling it was thought too sensitive. A lifting keel was regarded not fit for the south Atlantic. Even an ordinary fixed fin keel was ruled out as being, on one hand, too deep for inland waters, and on the other hand too vulnerable for ice or grounding.

Same with a spade rudder; for an expedition yacht such a rudder would be too sensitive and would not offer any realistic back-up solution in the event of a failure.

Please note that all these concepts are fine for almost any boat and we use most of them all the time. Only, this particular yacht was supposed to be able to be fine and safe in the most remote parts of the world, on her own, and under any conditions.

Efficiency to windward

Shoal draft keel, protected balanded rudder, daggerboards

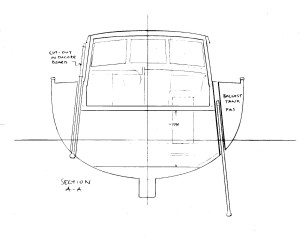

Finally, a somewhat unique concept grew on the drawing board: The boat would be built with a long, very shallow keel, extending all the way aft to protect the propeller and support the rudder. This would be the backbone of the yacht and allow a reasonable position for approx. 12 tons of lead ballast.

The rudder would of course be balanced in order not to strain the helm or autopilot too much. It would be at the same time be fully supported by the keel with a lower bearing, and fully protected by the same keel. This also meant that the controllable pitch propeller would be fully protected, and the propeller would be very close to the rudder for superior handling in port.

On the outside of the engine room each side, through the side decks, there would be asymmetric daggerboards. These would provide a lift to windward equivalent to a modern fin-keel yacht with 2,8 m draft. If one of the daggerboards got damaged in the Antarctic, the yacht would still be able to keep sailing. She would lose that last edge to windward, but that would be all.

Add stability

Bunker diesel to windward, daggeboard down to leeward

Outside of the dagger boards, towards the hull sides and under the side decks, this would leave an empty space each side. Unless we put ballast tanks there. But the boat wouldn’t be happy in freezing conditions with freezing water ballast, no matter if it was fresh or salt, so we decided to use this space for spare diesel bunker tanks. 2000 litres, to be half in each tank, or all on the windward side during a passage.

Again, with the combined stability gained by the filled windward tank together with the lead keel, this would provide the equivalent kind of righting moment that one would expect from a modern fin-keel yacht with 2,8 m draft. Voilà!

If the spare diesel had to be used she would lose some 10% of her sail-carrying ability but apart from this slight loss of performance, her safety or comfort would not be compromised. So, essentially, we were creating a totally safe yacht with 1,6 m draft that would behave like it had a modern cruiser-racer fin keel 2,8 m deep.

As dry as possible

Maybe the real beauty of this concept is the ability to dry out. The dagger boards serve as perfect legs. And the yacht would in such case rest on its keel bottom, not on the hull itself. In contrast, drying out with a lifting-keel boat could be a nightmare if you discover that the hull plating is sitting on a boulder. With the thick sole of this long ballast keel resting onto the sea bed, one will still be safe. Taking all aspects in account, we knew this design was as safe and amphibious and fast and simple we could come up with for a 40-ton, world cruising 64-foot sailing yacht.

It never turns out the way you expect

The ATOA was built beautifully in Enkhuizen, Holland. During the build, however, a decision was made not to build the daggerboards. We were very concerned, fearing that she would become a mediocre ‘motorsailer’ kind of yacht.

The 64′ as she turned out, with bunker ballast tanks

As it happened, the test sails with ATOA proved us all wrong.

In blustery, freezing conditions on the Ijselmeer she reached out of Enkhuizen at good speed, 9,4 knots, under reefed main and 106% jib. This was all expected, because even if she is on the medium to heavy displacement side of the scale, she is a slippery boat with a long waterline and a very fine entry. She was easy on the helm and felt nimble to handle. Everybody perched in the forward sheltered part of the cockpit or inside the pilot house.

As we headed up close-hauled, the speed dropped to 8,2 – 8,5 knots.The yacht made approx. 98 degrees between the tacks, counting leeway. Thus, she wasn’t very close winded, but she compensated more than well in speed. We didn’t even try to sheet harder and head up more – she had the potential, but speed seemed to be ATOA’s thing more than close-windedness.

Still, looking at the polar, with such speeds ATOA’s ability to windward would definitely take her anywhere, with panache.

The wind was a steady 24 knots, occasionally topping 28. Still with a reef in the main, we hoisted the mizzen. The speed increased by perhaps two tenths, she needed a little more helm and if the mizzen was sheeted hard the pressure on the wheel increased but still not enough to make steering heavy.

A little later, the diesel ballast was tested. It took around 4 minutes to pump the 2000 litres to windward, during which she righted herself from 18 to 14 degrees. She certainly felt powerful bearing away, again increasing to 10 knots, with little heel.

General Arrangement

The pilot house and the cockpit are closely connected, via a low staircase and big windows. The forward part of the cockpit is well protected under the overhanging roof and there is a huge dining space in the open or under the fixed bimini. Inside the pilot house are two sofas, with a coffee table and side tables. Visibility is excellent and under engine the yacht can be handled with ease from here.

Down the staircase forward, the emphasis is very clearly on the generous living room with its four areas – kitchen, dining, a lounging area and navigation. Forward is the owner’s cabin and bathroom. Facing aft, under the pilot house and between two watertight bulkheads, is the engine room which houses all major installations. There is good floor space and access to all installations and 1,57 m standing headroom.

Down a staircase aft from the pilot house are two smaller cabins, one en-suite guest double and a guest twin cabin. This makes use of the third bathroom which also serves as the yacht’s daytime w.c.

Forward and aft, accessible from deck, are two walk-in stow rooms.

Understanding a fast shoal-draft full keel yacht

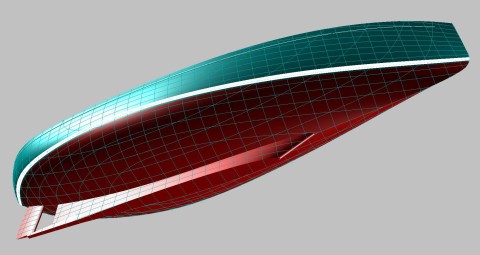

The ATOA’s performance on the wind was unexpected and of course tickled our curiosity. Somewhat later we had the opportunity to discuss our experience with Professor Lars Larsson at Chalmers University of Technology, in Göteborg, Sweden, and later to start a study on shoal draft keel concepts. The study was conducted by Andre Sauer under Professor Larsson and Michal Orych, comparing a thoroughly modern cruiser / racer with a deep keel and the same boat with a very shallow keel.

The two keel concepts were tested on two different hulls, one 20m long, one 10m. This time, the keel was given a slightly more sophisticated shape, with a bulb gradually turning into an beaver tail kind of end-plate back at the rudder.

The results, in short, are that the boat with the shallow keel still sails rather well. Even to windward.

Study of deep fin vs. shoal, full keel

As expected, the shoal-draft VMG (windward ability) is certainly inferior to the deep-draft boat. Still, I am not convinced that such extremely shoal draft would work as well for any boat: Our hypothesis is that it only works well for relatively large and slippery yachts. That the efficiency of this inefficient keel is very speed-dependent. There is room for further research on this.

I am not advocating anything here. Personally, I have a very soft spot for fast and responsive boats. On the other hand, giving away half a knot may perhaps be acceptable if you are going at around 8 or 9 knots anyway – especially taking into account the way most boats are used, very shoal draft keels could perhaps be a serious option for some. There are lovely cruising grounds with limited water… being able to enter more or less any harbour may be worth a lot more than losing that half knot.

It is interesting to contemplate this as you take a look at the market: More or less every boat has a kind of deep draft fin keel – be it fixed, lifting or swinging. If you set out to search the Internet for data on a thousand different sailing boats, chances are that you will not find a single one equipped with a fixed keel of such shoal draft that there is almost no keel there at all. Still, I think the ATOA shows that this may be a sensible option.

You can read more about the shoal-draft research here