YACHT RACING IN THE EARLY 1900s

Cannot resist a Duesenberg

Sailors are not only rational people but have sentiments, too, and while many are drawn to ultra-light racers on foils, others wouldn’t go to sea in anything less than a heavy pilot cutter. But some sailors feel that the most attractive yachts were built between the wars when the perfect cruiser was at the same time a flush-decked racing yacht. This was in the days when even cars and motor yachts had style and the owner of a major racing yacht in Long Island Sound would go to his office downtown in a Duesenberg or, in summer, in his fast commuter.

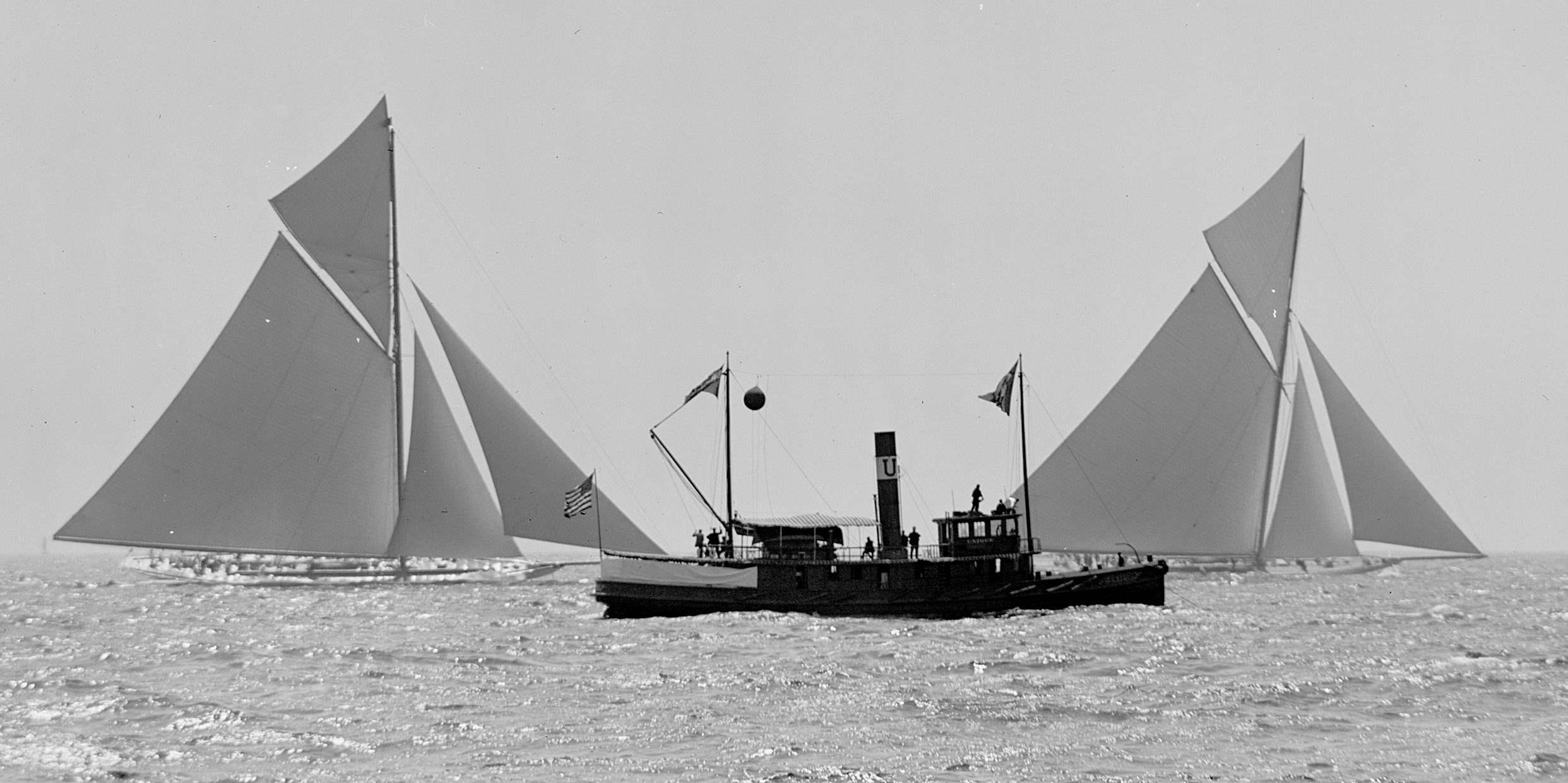

In those days, around-the-buoys racing usually took place in those slender, white, gleaming one-off, flush-decked yachts with their billowing cotton sails. The Gold Cup was one of the desired trophies, the racing grounds changing between Hankö, Cowes, Genua and Sandhamn; while the America’s Cup was raced off Newport, Sir Thomas Lipton challenging Mr Vanderbilt.

These one-off yachts obviously didn’t just come in any size or shape but were designed to a measurement rule, the idea being to assure that the speed of the yachts would be more or less the same, in spite of different length, sail area, displacement or other characteristics.

In international racing, two rules became dominant in the beginning of 1900:

The Universal Rule, devised by the great Nathanael Greene Herreshoff of Bristol, Rhode Island in 1905, was used for the the huge America’s Cup contenders, including the J-boats raced in America’s Cup until 1937.

The International Rule was first laid down in 1907 by British and Scandinavian naval architects in collaboration with German and French and produced a number of “Metre” class yachts – the 6-metres, 8-metres, 10-metres and 12-metres were some of the most prominent classes. These yachts were raced in the Olympics and, when the America’s Cup was resumed again after the war, 12-metres replaced J-boats in the 1958 Cup.

Sans Atout, 1912

I don’t have much of a personal bond with Metre Yachts even though it seems to run in the family. In the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm, Bengt Heyman won a silver medal in his 8-metre ‘Sans Atout‘, designed by Norwegian Johan Anker.

Another and very close relative, my grandfather Hugo Heyman, bought the 6-metre ‘Borgila‘ in 1925. Borgila was designed by Charles Nicholson and built in 1924 at Ängholmens Varv for a consortium at the Royal Yachting Club in Gothenburg, GKSS. Borgila was first owned by shipowner and Naval Minister Dan Broström but was bought by grandfather Hugo H after Mr Broström suddenly died in 1925, only 55 years of age.

Hugo Heyman

Both Mr Broström and grandfather were active members of GKSS but the two gentlemen knew each other from business as well, because Hugo Heyman was one of the driving forces in the development of Götaverken, the great ship yard in Gothenburg. Dan Broström was the biggest shareholder of the yard and his shipping company Broströms ordered most of its ships from Götaverken.

Let’s not try to wind the world back to those days but it seems the world was smaller then, and Sweden was perhaps a bit bigger. Götaverken was the world’s largest shipyard in the 1930s and Hugo Heyman was later CEO of the yard, after the war.

Borgila, 1924

Anyway, grandfather Hugo Heyman kept the 6-metre Borgila until the late 1940s.

Like most 6-metres, Borgila was probably fine for taking the family out on a sunny Sunday but very very wet in a blow. My father who was a keen sailor described her as a torpedo with sails, running right through the short, choppy waves in the Kattegat.

I was born a little too late to remember her. But nothing of all this has anything much to do with the following design, anyway:

______________________________

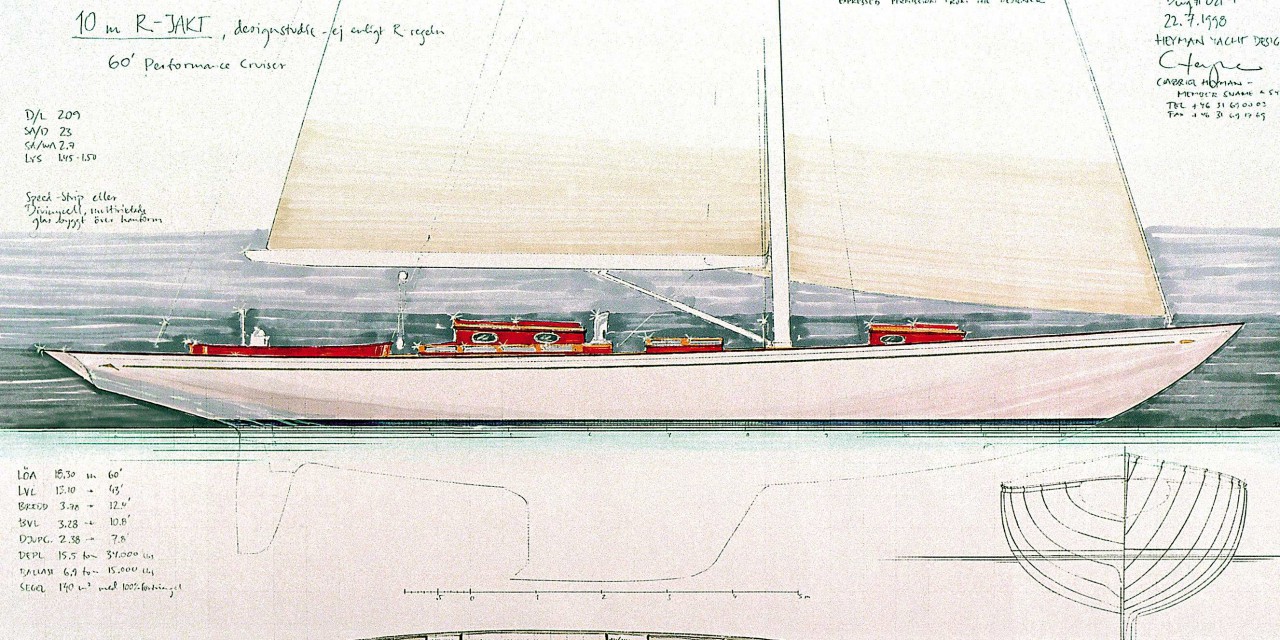

A 10-METRE CLASSIC

(however not a racing yacht, and not according to the International rule)

Design study for a yacht of an era when times were not necessarily better,

and boats were not necessarily inferior

This design study was made in 1998, inspired by sailing clients and boat builders talking dreamingly about long, sleek yachts of the past. Being asked for my opinion of such yachts I would usually take time to explain why boats of more moderate proportions make more sense. Still, things are never that simple and the perfect yacht does not come in one shape only.

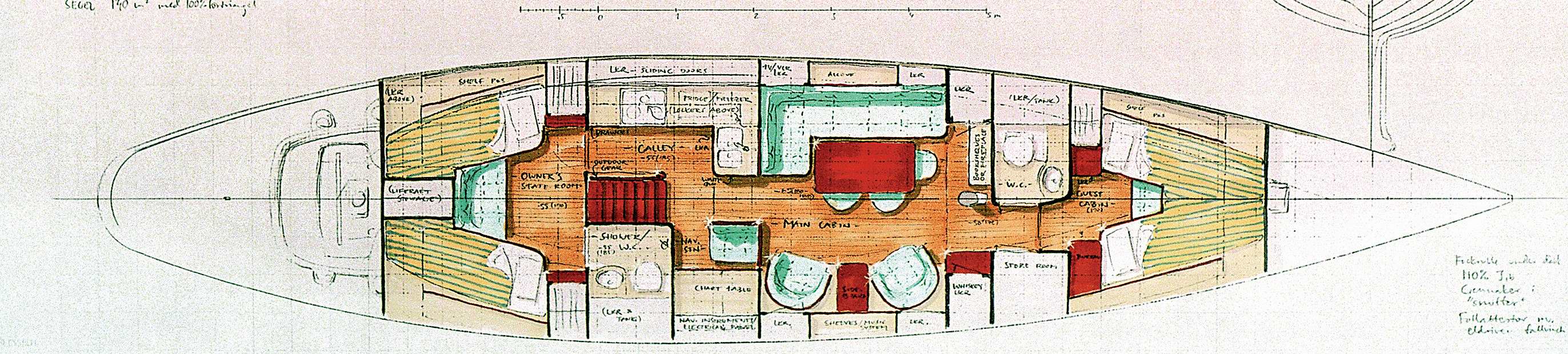

The merits of a narrow yacht with long overhangs can not be understood if it is simply compared to other yachts of the same overall length. Yachts of this kind should instead be compared to others of the same displacement or waterline length. This design is 60’ long, has the interior of a 50’+ Classic and sails like a sub-50’ modern cruiser-racer but with more easy, predictable handling qualities.

Racing in 10-metre yachts would certainly be an overwhelming experience. And if built on similar hulls, keels and rigs and with equal distribution of weights they can certainly be raced against each other. But the real beauty is that they would be equally suited for just ghosting along without much fuzz an afternoon when you simply cannot resist the breeze .

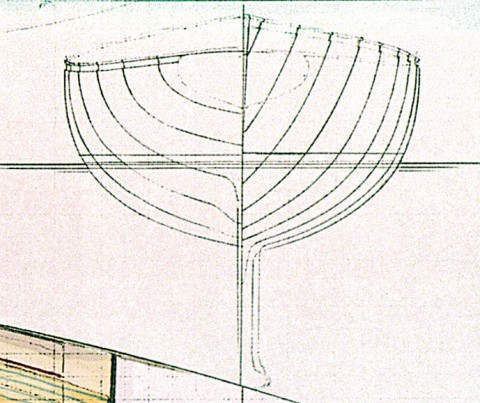

The main differences between this design and an old-time 10-metre are in the hull shape and materials, and these differences are so great that the two basic types of boat will show vastly different characteristics:

Hull shape will not be confined by the old rule which dictated extremely narrow yachts with deep, V-shaped sections. Being free of such restrictions the new yacht will sail more upright, will not have to be excessively heavy, will need less sail to drive her and she will have a lot more interior volume. And, since scientific evolution has not stood still during the last 80 years, the keel and rudder will be more efficient with less wetted surface, so she will be faster as well.

Hull shape will not be confined by the old rule which dictated extremely narrow yachts with deep, V-shaped sections. Being free of such restrictions the new yacht will sail more upright, will not have to be excessively heavy, will need less sail to drive her and she will have a lot more interior volume. And, since scientific evolution has not stood still during the last 80 years, the keel and rudder will be more efficient with less wetted surface, so she will be faster as well.

Hull building techniques including cored laminates with multidirectional rovings on PVC closed-cell foam core or, for a one-off hull, strip-planked red cedar. Whatever technique chosen, it will produce a hull with a quality, strength, stiffness, impact resistance, sound insulation, thermal insulation and low weight that simply was not conceivable in the old days. In addition, bulkheads and other large panels should be cored in order to bring unnecessary weight down. And a more modern rig and sails, with a carbon fibre mast in particular, will improve the yacht’s stability and motion in a seaway.

Looking back at this design now in 2016, almost 20 years later, there are a number of details I stumble upon. In order to preserve her standing headroom without making her unduly high, I think she ought to be a little longer overall, which would also allow her superstructure to be made a little lower. Apart from that I feel her counter stern should be longer, and her bow shape needs more character. My tastes appear to have changed over the years but she was also nothing but a quick draft when I made the design. I think, today, I would have made her between 64 and 68 feet.

In all, despite any rational objections one might have against classic yachts of her kind with slender hull shapes, flush decks and long overhangs, this design should prove functional and very rewarding to sail.

And, given some work, she could also be made beautiful to behold.

A yacht of this kind could be built by any skilled European or North American yard but, because of the character of the design, it only makes sense to go for the best finished, highest quality product.

SPECIFICATIONS

Dimensions:

L.O.A. 18,30 m 60,0’

L.W.L. 13,10 m 43,0’

Beam, maximum 3,78 m 12,4’

Beam, waterline 3,28 m 10,8’

Draft 2,48 m 8,1’

Displacement 17000 kg 37500 lbs

Ballast 7200 kg 16000 lbs

Sail area (100% fore triangle) 145 m_ 1560 sq.ft.

Ratios:

D / L 214

SA / D 22

SA / WA 2,7