Why a double-ender? – Traditions behind the 39’ Pavane

This double-ender stems from a type of coastal fishing boats which were common in Scandinavian waters during the past centuries. It would be much too far-fetched to claim that they are all descendants to the long-boats of the Vikings, but in fact I guess this is where they have their roots. However, over the centuries, they have developed in different directions.

On the Swedish west coast and in Norway, the double-enders, called ‘koster’, had a dramatically full bow and a rather slender stern. The smaller boats were clinker built, had outboard rudders and were used as coastal fishing boats, later equipped with engines. The larger ones were often carvel built. A somewhat refined variety of the west coast koster are the ones later developed by Colin Archer into his hefty rescue boats, ‘redningsskøyte’.

In Denmark and the southermost parts of Sweden, the double-enders had very different proportions, with full-bodied sections aft, making them more buoyant. With their more balanced shape forward and aft, the spidsgatters balanced well when heeled and were able to take a storm on their quarters without being pooped. The lines of spidsgatters were a little more ‘yachty’ in appearance, they were most often carvel built and usually a little quicker as well.

There were two different kinds of sterns, characterised by their rudder arrangements. The most common was the outboard rudder which was always used for the smaller boats. The more unusual ‘kanothäck’ or canoe stern had the rudder post pass through the hull. This arrangement was used for some of the bigger double-ended workboats but even then it was rare, until a hundred or so years ago, when canoe sterns started to appear in two vastly different types of double-enders: In bigger fishing boats and trawlers, and in yachts. Canoe stern yachts of a similar kind were also somewhat popular in Britain and, to some extent, in Germany but – dare I say so – they were never as lovely as the Danish ones.

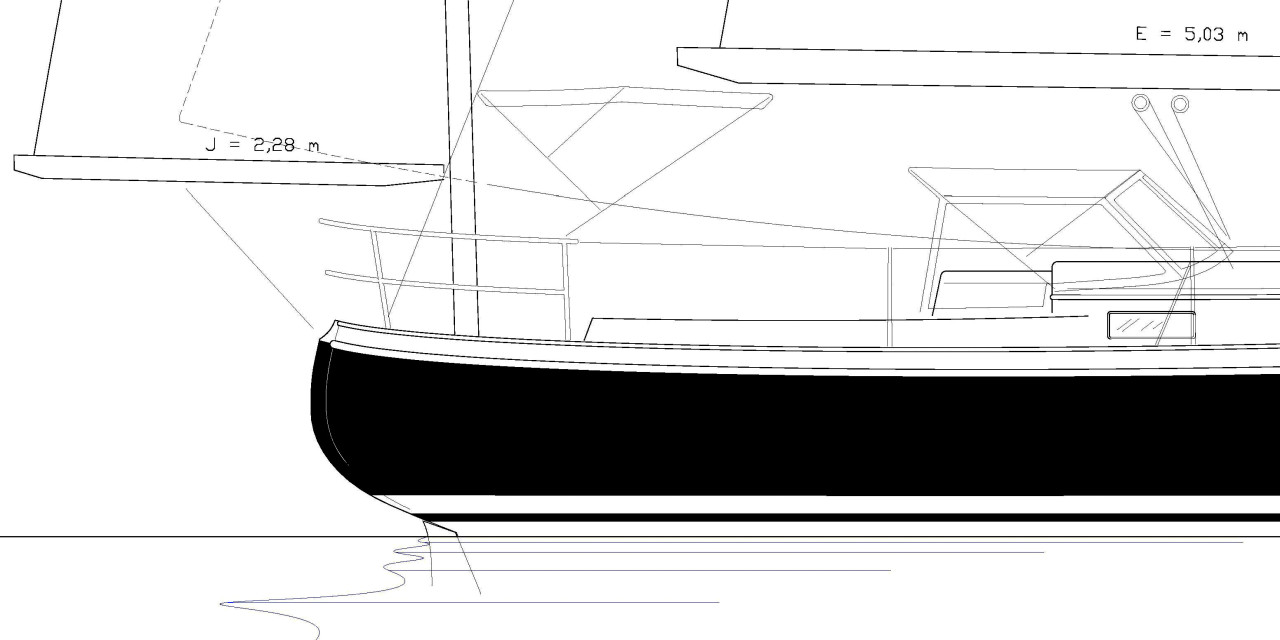

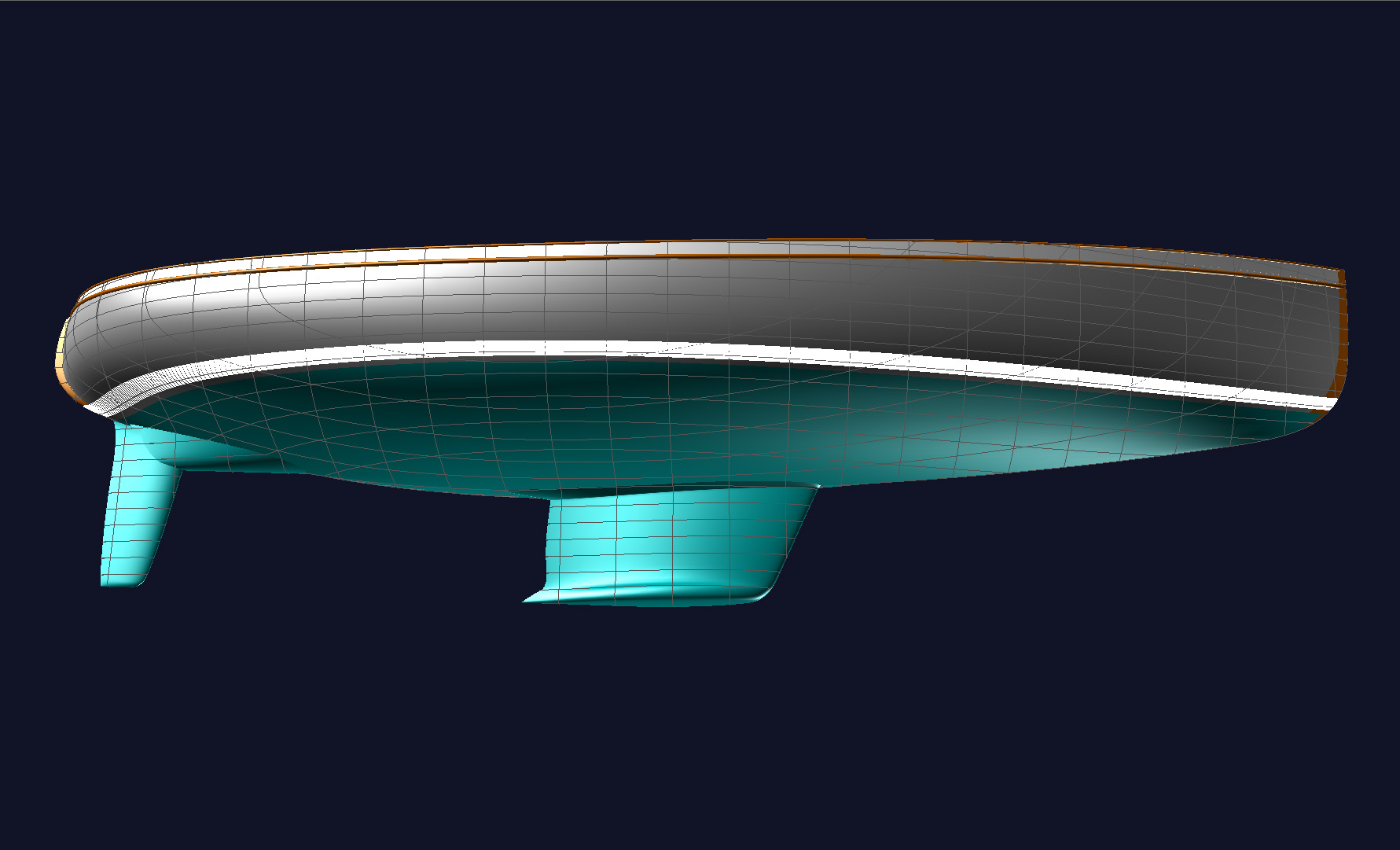

The inspiration for the 39’ Pavane stems from these lovely, wholesome spidsgatters and Øresundskosters of the southern Baltic, with a side look to early/mid-1900s yachts by the likes of Berg, Reimers and Aage Nielsen. Personally, I think her traditional lines above the waterline go together extremely well with her modern hull shape under the surface – a happy marriage of styles and shapes, separated by a century.

A modern, slippery cruising yacht

This design should be equally at home on a mooring on the Clyde, in Newport or in Cannes. She is intended to be a manageable boat, able to sneak in almost anywhere. Under sail, she will provide fast passages, averaging between 7 and 8 knots on all points of sailing but at the same time, will be seaworthy and well behaved.

Cruising life is changing. I guess most people think of cruising as heading for another shore, exploring new anchorages. But cruising could just as well mean day sailing to a familiar port, visiting a nice restaurant, meeting friends. And while many crews consist of a couple, most will also want to invite friends or children to join them for a week or two. And, even with only two on board, most people will want some basic comfort, and stay in contact with the world beyond.

Therefore, I believe a proper cruising boat will be one that her owners will never find too cramped, too slow, too cranky or too limited. She will have to offer much more than just being a good sailing boat for two.

Still, at below 40 ft., and being of moderate proportions, this design will be easily handled. But this is not about size only. It is perhaps more about clever use of space, a long water line, an efficient hull shape, and about avoiding unnecessary weight or complication.

There is another aspect to the matter of size and cost:

The earlier 36′ design

The cost of a boat will be a function of its weight. But the cost of building a one-off will also be a function of its surface areas, as all surfaces are finished by hand. Comparing, for example, a 30 ft one-off with a 39 ft., the bigger boat will have 70 % more surface to finish but she will offer 110% more space. For a one-off, the slightly bigger boat, not too heavy, is more cost-efficient.

Provided, again, that she is designed to make efficient use of her size.

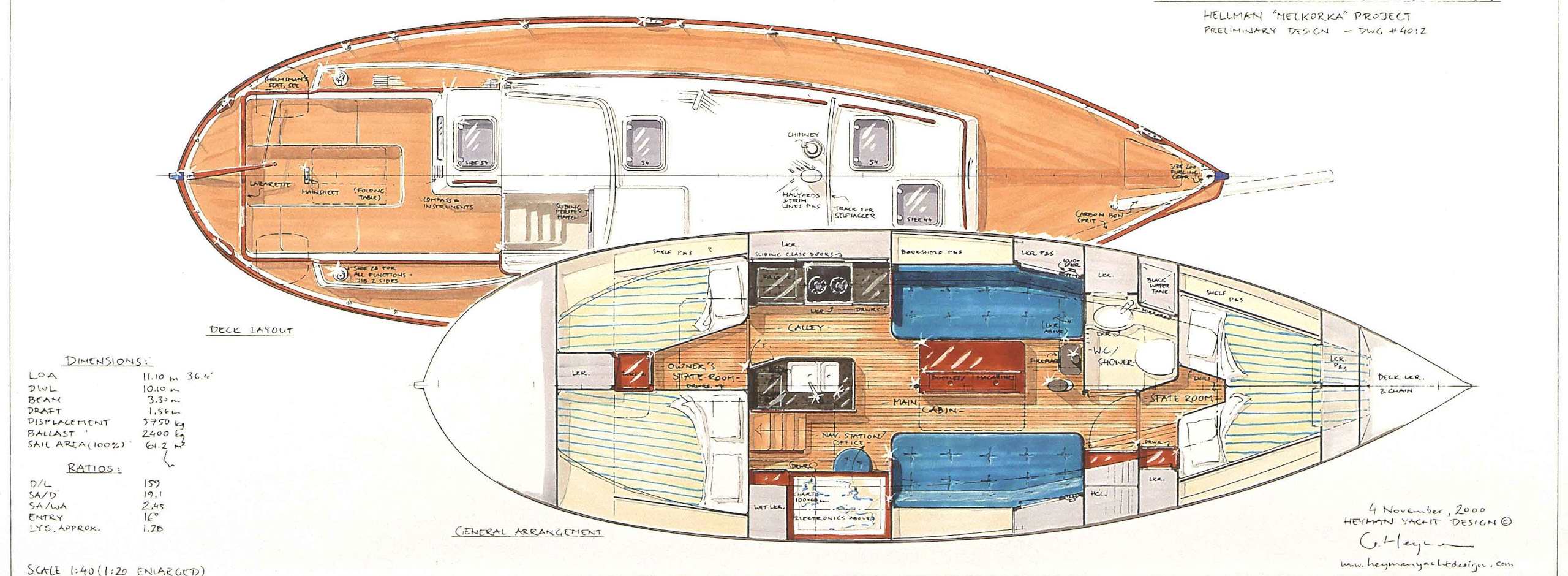

The design for this 39′ yawl was finished in 2012 and was developed from a 36′ sloop, designed some 12 years earlier. This lovely yacht is a one-off build, made from strip planking and sheathed in multi-directional glass and epoxy.

Under water

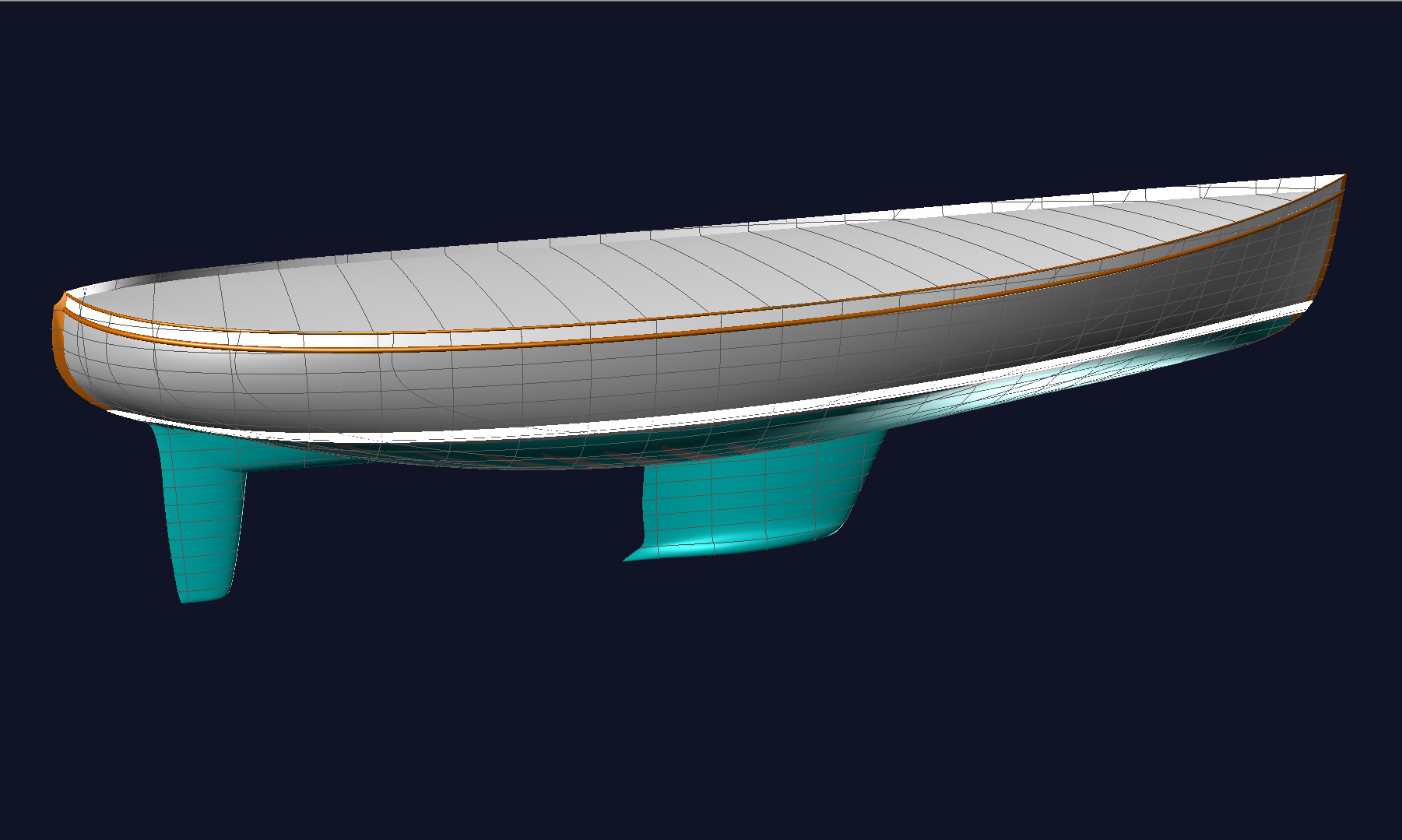

Pavane’s hull is very slender, and unusually sharp forward. Her volumes are pushed aft and she carries her fin keel further aft than most boats, which helps make her directionally stable and easy on the helm. The bustle or skeg in front of the rudder helps a little as well.

Pavane’s hull is very slender, and unusually sharp forward. Her volumes are pushed aft and she carries her fin keel further aft than most boats, which helps make her directionally stable and easy on the helm. The bustle or skeg in front of the rudder helps a little as well.

A full keel was avoided for simplicity, cost, and speed. But it should be noted that this does not make her inferior in terms of safety, or steering. In addition, the fin keel makes manouvering easier.

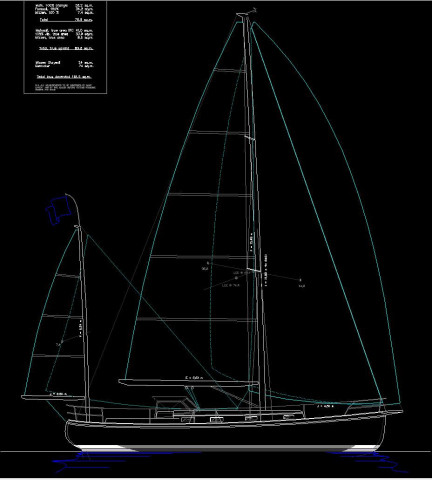

OK, but why a yawl rig?

39′ Yawl Rig

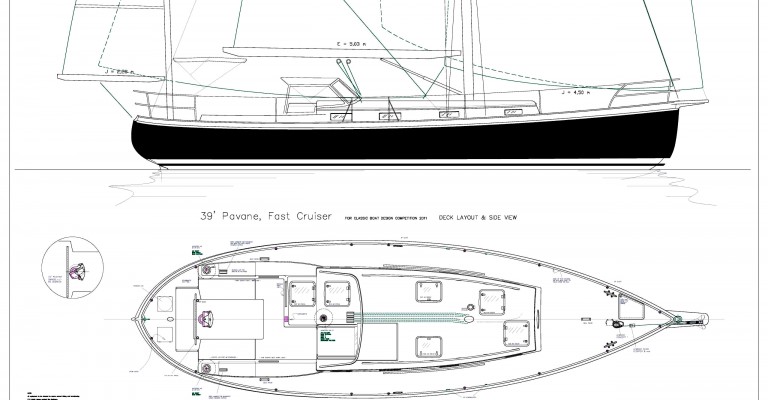

By definition, this rig would probably be called a ketch but the sail plan is that of a yawl. The distinction between yawl and ketch is based on the mast position in relation to the rudder stock; this is the formal definition. But considering the sail plan proportions of this particular design, with its smallish mizzen set far aft, I have chosen to call her a yawl.

The mizzen mast is unstayed, the mizzen is tiny and contributes nothing on the wind. On the other hand, it is not really in the way either. On a reach, it gives a little extra push, especially with the staysail set. When anchoring or approaching a mooring, it keeps the bow into the wind, even at zero speed. And in a sudden blow, one can romp along under a deep-reefed jib + mizzen.

Layout

The helmsman sits aft and the forward part of the cockpit, if you like, is for enjoying the day, eating, reading – or sleeping. The starboard seat is extended a little further forward, leading to the entrance.

Inside, there is a big hanging locker and a navigation table. Rounding the central island, one enters the galley. There is good contact with the cockpit through the entrance hatch and the opening portlight on the port side. The engine is accessible from all sides, under the galley sink, and the fridge is opposite, under the navigation table.

The aft cabin is unusual for a boat with an aft cockpit and is intended as the owner’s cabin, laid out for a couple. There is standing headroom, one can sit down on the berth and move about in a dignified manner.

There is stowage for two folding bicycles behind the backrests in the main cabin.

The forward cabin will accommodate guests without disturbing the owners. But, during periods when the yacht is used by its owners only, this area can be used for other purposes, for stowage, or as an office.

Construction

A strip planked red cedar hull is encapsulated in multidirectional glass and epoxy, making for a light, strong and durable structure. Alternatively, a Divinycell foam-cored construction has its merits.

Drawings

Dimensions

- L.O.A. 12,00 m 39,4′

- D.W.L. 10,73 m 35,2′

- Beam, maximum 3,46 m 11,4′

- Beam, waterline 2,89 m 9,5′

- Draft 1,64 m 5,4′

- Displacement, light 7200 kg 15860 lbs

- Ballast 2600 kg 5730 lbs

Sail areas

- Sail area 100% 76,8 m² 827 sq.ft.

- True sail area 83,5 m² 899 sq.ft

- Mainsail, true area 41,0 m² 441 sq.ft.

- Jib, true area 33,9 m² 365 sq.ft.

- Mizzen, true area 8,6 m² 93 sq.ft.

- Gennaker 74 m² 797 sq.ft.

- Mizzen staysail 24 m² 258 sq.ft.

Ratios

- D/L 165

- SA/D, upwind 20,6

- SA/D, downwind 48,7

- Entry angle 14,7 °

Security

AVS 131 °

Downflooding 102 °

CE Category A (Ocean)